Microaggressions are in the news, nationally and locally. In a recent New York Times piece, “Students See Many Slights as Racial ‘Microaggressions,'” Tanzina Vega describes microaggressions as “the subtle ways that racial, ethnic, gender and other stereotypes can play out painfully in an increasingly diverse culture.” The concept isn’t new. It was developed in the 1970s by Dr. Chester M. Pierce, a professor of education and psychiatry at Harvard University, to describe the “subtle, cumulative miniassault that is the substance of today’s racism” (qtd by Brockenbrough). Common parlance among social scientists and critical race theorists, microaggressions have recently spread from the higher echelons of academic discourse into the mainstream, causing a stir even in the bubble of tranquility that is Davidson College.

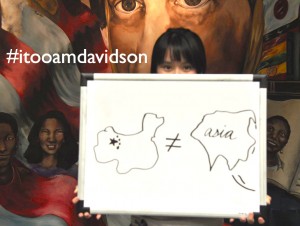

Inspired by a Tumblr blog at Harvard University, students here have created their own Tumblr, I, Too, Am Davidson (echoing Langston Hughes’ “I, Too, Sing America“). Standing in front of the new mural depicting the College’s multicultural history, they hold signs citing microaggressions like, “After a party, the police stopped me and said, ‘Hurry up and get to your car and go back to your school.'”

Inspired by a Tumblr blog at Harvard University, students here have created their own Tumblr, I, Too, Am Davidson (echoing Langston Hughes’ “I, Too, Sing America“). Standing in front of the new mural depicting the College’s multicultural history, they hold signs citing microaggressions like, “After a party, the police stopped me and said, ‘Hurry up and get to your car and go back to your school.'”

Microaggressions may elicit shock, disbelief, anger, isolation, alienation, fear, shame, or any combination thereof. But as poet Claudia Rankine observed in her recent talk at Davidson, a victim’s response is often delayed. The immediate reaction tends to be silence.

Rankine explores this effect in her latest work, Citizen, a documentary prose poem that collects microaggressions from her own experiences and from interviews, such as this one:

You are in the dark, in the car, watching the black-tarred street being swallowed by speed; he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there.

You think maybe this is an experiment and you are being tested or retroactively insulted or you have done something that communicates this is an okay conversation to be having.

Rankine uses the second-person “you” to put you, the reader, in the place of a microaggression victim. The use of “you” isn’t just a strategy for arousing empathy, however; it is also symptomatic of psychological alienation experienced by the victim who, instead of responding to the offender, goes silent, turning inward and questioning herself.

Rankine’s goal, she said, is to shorten the response time—that is, to offer language that may empower people to respond immediately and vocally to microaggressions, in order to promote healing and understanding.

In seeking to break the silence, Rankine’s experimental poetry is like the microaggression blogs (even if it doesn’t get as much internet traffic). Vivan Lu, co-creator of The Microaggressions Project, says the blog “gives people the vocabulary to talk about these everyday incidents that are quite difficult to put your finger on” (qtd by Vega). The blog testimonials are empowering acts of witnessing and protest: they allow people to assume ownership of damaging remarks, to reframe them, and to reverse the target. Contributing to a Tumblr may also replace feelings of marginalization and alienation with a sense of belonging to a community.

Athough these Tumblr sites are beneficial for the contributors, however, it’s less certain how much good they do for broader public discourse about race. Vega reports, “What is less clear is how much is truly aggressive and how much is pretty micro — whether the issues raised are a useful way of bringing to light often elusive slights in a world where overt prejudice is seldom tolerated, or a new form of divisive hypersensitivity, in which casual remarks are blown out of proportion.”

The concept of microaggression, by definition, does not imply intentional hostility or conscious racism. In Psychology Today, Derald Wing Sue and David Rivera define microaggressions as, “the brief and everyday slights, insults, indignities and denigrating messages sent to people of color by well-intentioned White people who are unaware of the hidden messages being communicated” [emphasis added]. Nevertheless, the term can lead to misunderstandings, in that it connotes aggression on the part of the microaggressor. From the Latin aggredi for “to attack,” the term aggression, even when miniaturized, doesn’t seem to allow for bumbling curiosity or hapless ignorance. For people unfamiliar with the social scientific definition who perceive themselves as implied offenders, the term microaggression may arouse defensiveness. “I hate the term microaggression,” I heard someone say, “it is itself a microaggression.”*

Which raises the question: are microaggressions reversible? This is a version of the controversial topic of reverse racism. My colleague Hilton Kelly, Associate Professor of Education Studies, who teaches courses on critical race theory, defines racism as “a system of advantages based on skin color.” He distinguishes racism from prejudice, the personal belief that one race is superior to another. Since racism is about deep-seated power inequalities, Kelly argues, it can’t be easily reversed. He offered the example of a white woman going to black nightclub, but feeling unwelcome and overhearing hostile remarks about her presence. Is this reverse racism? No, because the system still favors the white woman. As soon as she steps outside, who’s on her side? Whose side is the police and criminal justice system on? There may be prejudice the black nightclub, but it’s not racism unless it’s reinforced by a system of advantages based on skin color.

Okay, I said, but let’s take a local example: what about a black fraternity here at Davidson that won’t accept a white student? Kelly replied: “I’d need more information to respond to that question. For instance, I’d need to know, why is it that no one has asked the same questions about similar practices by white fraternities that went on for decades?” That’s not just a good point, I think; it’s good practice: ask for more information. Like racism, microaggressions aren’t reversible, but asking for more information is.

In my class the next day, when we’re scheduled to discuss Rankine, racism, and microaggressions, we start with an experiment. We stand in a circle and first identify our “triggers”: those remarks, attitudes, or behaviors that arouse anger and defensiveness, and shut down conversation about racism. Then we go around again and identify, “openers”: remarks, attitudes, or behaviors that encourage us to talk openly with each other. After we finish, one student observes:

Isn’t it interesting that our triggers are all different, but our openers are the same?

It’s a profound moment. Wow, I think, we’ve done it: we’ve broken through to a way we can talk openly about racism at Davidson.

Not so fast. A student raises the issue of affirmative action, asking if it is racist for positions to be taken away from whites and given to minorities. “Hmm,” I say, echoing Kelly: “I’d need more information to know if that’s racism. For instance, I’d need to know, why is it that no one complains about how many places were taken away from minorities and given to whites over the decades?”

“Good point,” someone murmurs.

The point isn’t mine, of course, and neither is the practice. But it is a good one. Instead of getting angry, try saying: I need to know more.

Take this example from the Davidson Tumblr, where a student makes the reasonable request, “Please stop asking why I can’t tolerate spicy food.” Presumably she’s been asked countless times, “Why don’t you like spicy food?” And she’s understandably annoyed by the question. But let’s reimagine that irritating encounter by applying Hilton Kelly’s approach:

— “Why don’t you like spicy food?”

— “That’s an interesting question. Why do you think I would like spicy food?”

— “Because you’re Asian.”

— “Asia’s a big, diverse continent. I wonder if tastes are consistent across any continent. Do you think North Americans like bland food?”

Is this approach putting more burden or responsibility on the minority? Maybe. But it’s also “shortening the response time” and giving everyone, including minorities, an opportunity to get beyond anger, and come to a greater understanding of the triggers that divide us and the openers that can bring us together.

And who knows? Maybe someday somebody will start a Tumblr, #NeedToKnowMore.

*The person who made this statement preferred not to be named, believing that openly expressing skepticism about the term microaggression would only incite more anger and resentment. This fear of reprisal reflects the polarizing effect the term can have: in this case, it foreclosed conversation.

Works Cited:

Brockenbrough, Ed, Ph.d. “Microaggressions: Conceptual Foundations.” Warner Graduate School of Education, Rochester University. Dec. 3, 2010. Accessed April 21, 2104.

I, Too, Am Davidson. Tumblr Blog. Accessed. April 13, 2014.

Kelly, Hilton. Personal Conversation. Summit Coffee House. Davidson College. March 20, 2014.

Sue, Derald Wing, Ph.D., and David Rivera, M.S. “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life.” Psychology Today. Published Oct. 5, 2010. Accessed April 21, 2014.

Vega, Tanzina. “Students See Many Slights As Racial Aggressions.” NewYorkTimes.com. May 21, 2014. Accessed April 13, 2014.

Hi Suzanne——-Our personal experience re racism and religious discrimination is that it is connected to power and fear. Fear of the unknown and persons feeling because of the colour of their skin or their religious beliefs they deserve power over the “other”. We never have understood either concept. Our technique in dealing with all of this is to always “name the elephant in the room” and to speak about our beliefs as kindly as possible. I remember also a friend telling me she hated people who were on welfare–at that time one of our daughters was living on welfare!!! I just remember thinking–be very careful what you say as it may hurt the person you are talking to. You will laugh because today brian was told he is going to Hell because he does not believe the Bible literally. His response–“oh good—— all my friends will be there!!!!!”! —Here is to humour and naming elephants!!!–love jean