When your mother has just died, people come up to you with empathetic eyes and soft voices and ask, “How are you?” So genuine is the concern that I feel like I should burst into tears and confess that each day is a trial, that I feel as if I’m plodding through mud, dragging my sinking heart behind me like a heavy stone.

Instead, I admit, I’m doing surprisingly well—so much so that I wonder if my heart has become a cold stone. Ads for the just-released movie Wild deliver a subtle subtext to me: What’s wrong with you? Shouldn’t you be plunged into your own journey through the dark wilderness of grief? Shouldn’t the death of your mother leave you feeling lost, unmoored, and ravaged by unrelenting grief?

It hasn’t. Maybe I’ve already traversed that wilderness, as I hiked the long, meandering trail of Alzheimers, where the decline was so slow and relentless that I didn’t see the dark forest through each withered, falling tree. Maybe I’m further along the path of grief, past the deep gullies and sharp cliffs. Ok, so I needn’t be ravaged by grief, but why do I feel happy?

Watching Mom slowly deteriorate was so agonizing that I was unprepared for the relief I would feel when I no longer had to face sight of her unable to speak, walk, or even wake up. Now that she’s dead, I can begin the business of letting go of those tortured images and re-collect earlier memories of her, when she was full of life.

My sister-in-law set this process in motion when she sent me a Mead writing tablet (100 plain sheets), with the yellow Renys price tag of 79¢ still on it, which she’d discovered in a box of art supplies. Mom had purchased the notebook to write down stories she’d composed for her grandchildren, documenting their activities at the cottage in Maine and their New England excursions. There’s a story about Benjamin “who loves a very special lake in Maine,” and another about the “happy, noisy times” the four cousins have together during winter and summer vacations, which begins:

This year during Christmas week, 1999, Ben who is 7 3/4, Alex who is 4, and Luke & Thomas are 3 had fun day with their grandparents Nanu-Nana & Granu (Wintsch).

Here’s Mom come to life in her loopy, left-handed, back-slanted handwriting and in the painstaking detail with which she records their exact ages, hyphenates the two names she’s called by her two sets of grandsons so that the story belongs to them equally, and inserts her last name in parentheses—for posterity, to keep the story alive for the next generation.

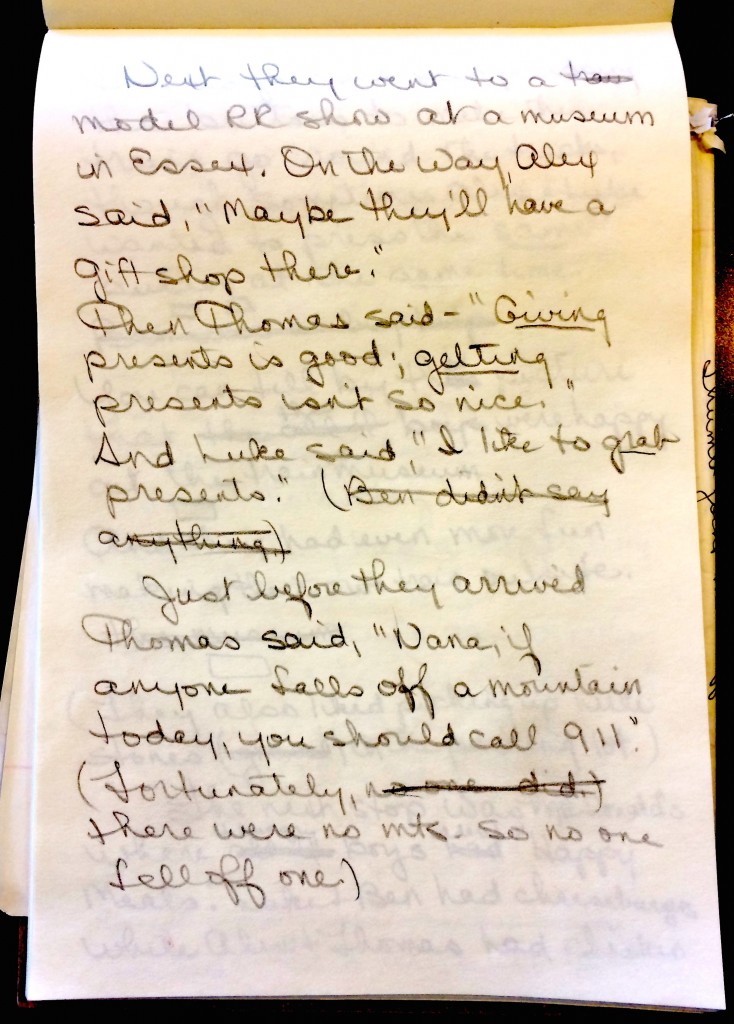

And then there’s her delight in the humor of their conversations, and her careful editing to perfect the timing of the punchlines:

When I read this story, I don’t feel like I’m falling off a mountain into “the valley of the shadows of death.” I laugh and remember my Mom as she once was, so beguiled by her grandchildren, and my kids as 3-year-olds: Thomas so judicious and perceptive, and Luke so full of appetite.

When I read this story, I don’t feel like I’m falling off a mountain into “the valley of the shadows of death.” I laugh and remember my Mom as she once was, so beguiled by her grandchildren, and my kids as 3-year-olds: Thomas so judicious and perceptive, and Luke so full of appetite.

Speaking of appetites, one of my favorite blogs is Maria Popova’s Brainpickings.org, a librarian’s buffet of delicious tidbits from good books. This morning I stumbled upon her post about Anne Quindlen’s A Short Guide to a Happy Life. When she was nineteen, Quindlen’s mother died of ovarian cancer—a devastating loss that paradoxically illuminated her universe:

“Before” and “after” for me was not just before my mother’s illness and after her death. It was the dividing line between seeing the world in black and white, and in Technicolor. The lights came on, for the darkest possible reason.

Quindlen insists on need to embrace death in order to live life fully. Like Wallace Stevens, who wrote in “Sunday Morning” that “Death is the mother of beauty,” she understands that mortality paradoxically gives birth to a fuller appreciation of life’s beauty. And like Mary Oliver, who in her beloved poem, “The Summer Day,” urges you to relish “your one wild and precious life,” Quindlen calls us to pay attention to the rich palette of the everyday world, to find beauty and joy in the mundane and minute:

Consider the lilies of the field. Look at the fuzz on a baby’s ear. Read in the backyard with the sun on your face. Learn to be happy. And think of life as a terminal illness, because, if you do, you will live it with joy and passion, as it ought to be lived.

It’s a morbid idea, to “think of life as a terminal illness,” but it helps me understand why I might feel a sharpened sense of happiness just after my mother has died of one.

Ben didn’t say anything. No one did.

HI Suzie—Beautifully written as always–and you have an amazing perception of the how and whys of life. My wise Father ( who just sat down one day in January 1984 and died instantly at age 75!!) always said–Never ask “why” as there is no answer–Just know you will always find the way through what ever life brings you.

I just sent a wee note to your Dad as I know it will be hard for him –each day. So we sent hugs to him over the miles as we do to you.

When Dad died I would have waves of grief come over me–it was all so sudden–but when Mother died at 102 ( I had begun to think she was immortal!!!) with dementia there was a sense of relief for me–and I too remembered what a wonderful, talented person she had been and a great Mother to me.

Now as I reach nearly 76, Brian and I enjoy each day as it comes, determined to remain positive and active. I know that will be for you also. You are special . Your Mother was special. love jean

Somehow I think Valerie would be pleased that you are appreciating the good in life, with your deeper appreciation of its impermanence. As you read more of our mom’s stories, let us know if Zac’s pick-up line, “So, do you have any trucks?” appears…

Hi again. I was thinking more about this post. Is the subtext of Wild (which I have not seen) really as you say? Wouldn’t that then mean that Quindlen’s subtext is that to “grieve right” one must be happy? I’m wondering if people can tell their tales without giving us subtext about what other people should do. Maybe the message from both sources is that we get through grief in whatever way works for us, and together they highlight that there are many possible roads through grief. Thanks for giving me food for thought!

Hi KM,

Thanks, as always, for your thoughtful and thought-provoking comments. I haven’t read Wild or seen the movie, so I can’t say anything about what its message is. What I meant about the subtle subtext was really the message I was projecting on the movie, based on what I’ve seen from the ads. From what I understand, the main character has had a difficult life and perhaps the most devastating trauma was the death of her mother from a long illness. She eventually hits “rock bottom” and goes on a recovery quest into the “Wild,” referring I assume, not only to the natural wilderness but also to the wilds of her own emotions. I don’t think Wild or Quindlen are telling us how to grieve–everyone’s process is different. I’m just trying to figure out my process, and Quindlen’s wisdom (lessons for life, rather than for loss) helped.

I am always astonished with the reaction I have to the handwriting of someone who has died, and was so moved when I saw your mom’s distinct handwriting. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and insights. Love to you and your family.