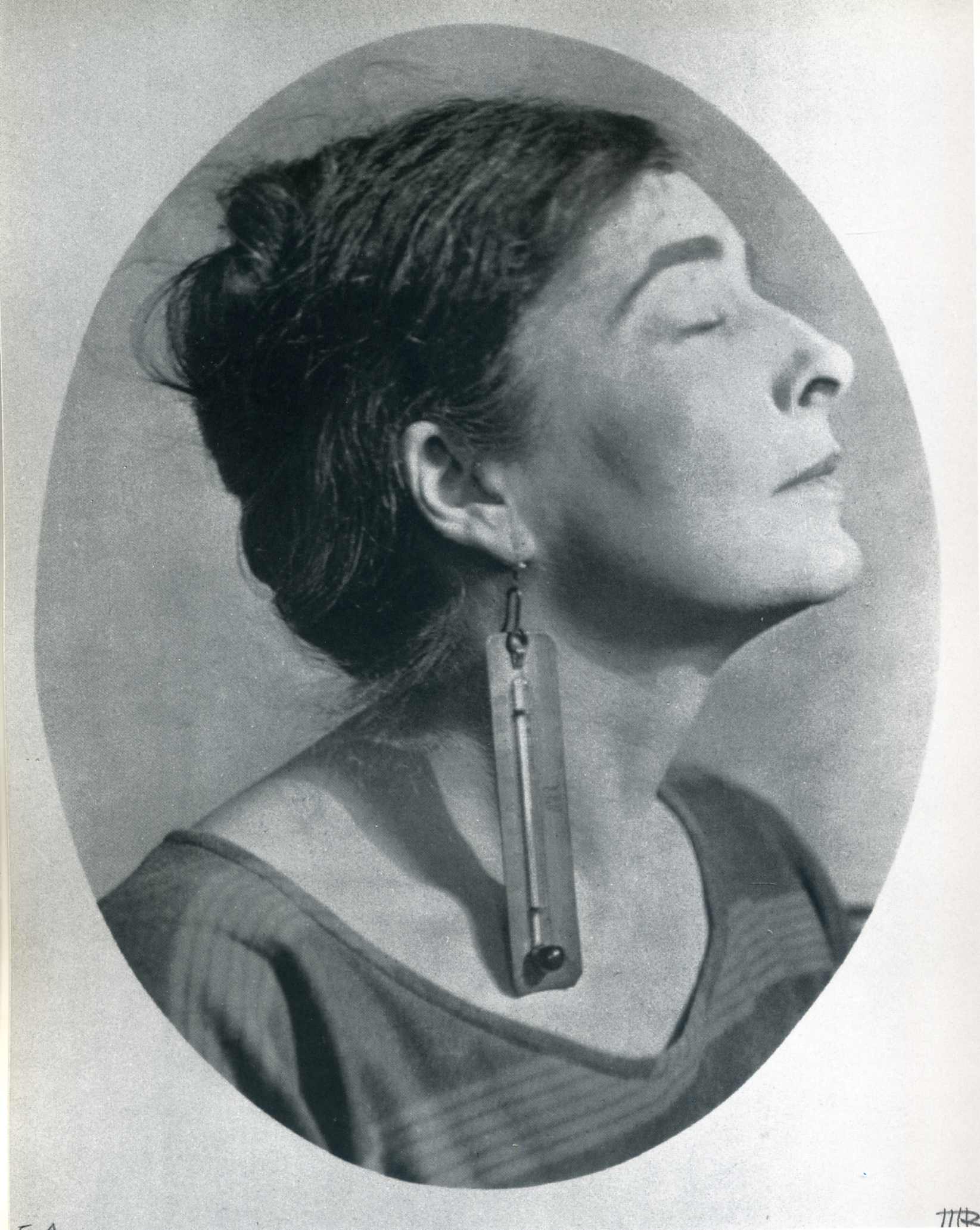

Chapter 1: Entree Mina Loy

This is the first chapter of my magnum opus on Mina Loy’s migration from Italian Futurism to New York Dada. First let me tell you who she was:

Artist. Writer. Entrepeneur.

Born in London to an English mother and German Jewish father, she was raised in an aspiring middleclass Victorian household. She did not fit in. Artistic, dreamy, and headstrong, she was the problem daughter. Her parents sent her to a series of art schools, first in London, then in Berlin, and then in Paris. In Paris, she was elected into the prestigious Paris Salon, and seduced by Stephen Haweis, whom she married. Disastrous. Then she moved to Italy where the Futurists woke her out of her lethargy and depression. Affairs. Also disastrous. Then she moved to New York, where she found more amorous, amicable relations in the Arensberg cirlce, a proto-Dada cadre.

Chapter 2: Futurist Serata

December 12, 1913. Five thousand spectators crowd into the Teatro Verdi in Florence, Italy, to witness an unprecedented event: a Futurist serata or “evening,” orchestrated by F. T. Marinetti and Giovanni Papini. The mood is electric. The theatre-goers are restless with anticipation, whetted by the flood of publicity spread around the city via posters, fliers, and newspapers.

Marinetti ascends the stage and launches a barrage of insults at the audience. The crowd erupts, hurling oaths, cheers, and rotten vegetables. Standing impervious to the chaos, Marinetti suavely catches an egg vaunting toward him and shouts back: “Your frenzied behavior gives me pleasure. The only argument the passatisti have is a horde of dirty vegetables” (qtd by Burke 156).

Papini takes the stage and attacks the entire city of Firenze for being “marked by the past as by a disease” and requiring “the fresh air of futurism” to rid it of the “disgusting passé-ists who make their home here” (qtd by Burke 156).

The crowd roars with applause. Somewhere in its midst, a tall, striking woman “with grey-blue eyes,” “waved black hair,” and “strange, long earrings” sits smiling, lips closed and eyes wide open (qtd by Burke 173).

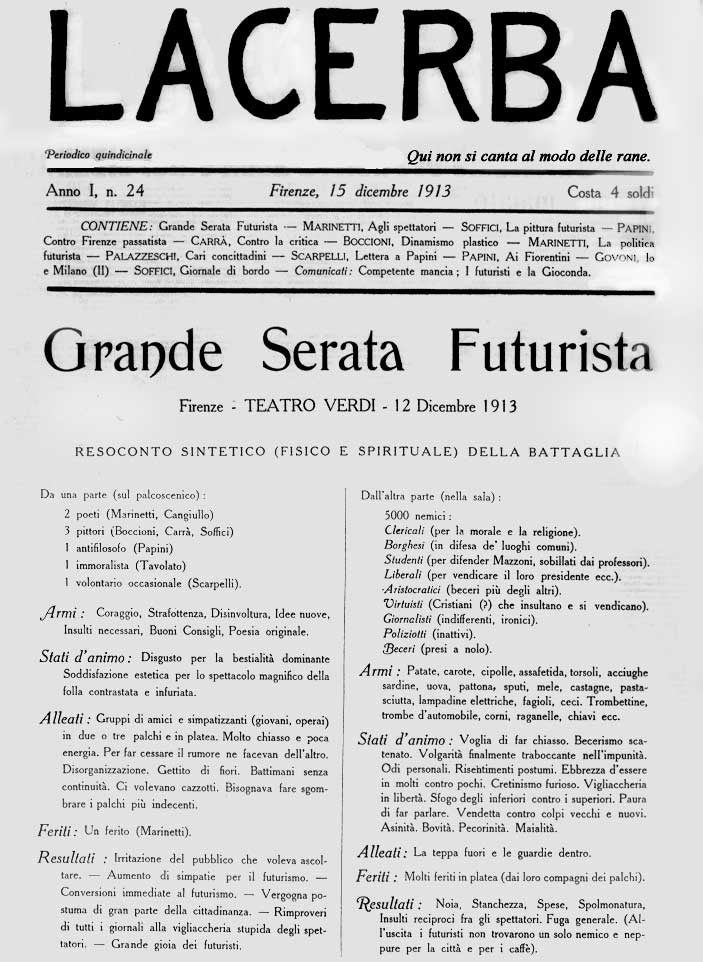

Chapter 3: Lacerba

Three days later, the Futurist newspaper Lacerba declared the event a triumph, proclaiming victory over the crowd, whose “overwhelming vulgarity… drunken frenzy… [and] raging stupidity” they had transformed into “a magnificent spectacle” (qtd by Burke 156). Mina Loy—the tall woman with strange earrings—shared their sense of accomplishment, feeling as cleansed and exhilarated by the event “as if she had benefited by a fortnight at the seashore” (qtd by Burke 156).

But she was not convinced that the Futurists controlled the crowd. She teased her lover Marinetti, telling him he had no identity apart from his audience: “Even there you are a spurious entity, drawing ‘something’ out of an audience to give back to them in your superb pretentiousness as yourself” (qtd by Burke 156). Far from having mastered the audience, she suggested, Marinetti was utterly dependent upon it for his identity and power. Her taunt must have struck a nerve, because he countered by forbidding her from attending any more seratas. He could not risk having the keen-eyed gaze of a woman puncture his ballooning sense of ascendency over the audience.

This anecdote, recounted by Carolyn Burke in Becoming Modern: the life of Mina Loy, complicates the oft-told story of Loy’s artistic and erotic entanglements with the Italian Futurists. Loy was powerfully attracted to the Futurists—so the story goes—she was electrified by their energy, but repelled by their misogyny (Burke 178-9, Arnold 84, Augustine 92, Schmid 1). Loy was entangled in a triangulated affair with Marinetti and Papini between 1913 and 1916, while she was living in Italy. When these affairs soured, she packed up and moved to New York for two years, shifting affiliation to a proto-Dada set that included Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Beatrice Wood, and the love of her life, fighter-poet Arthur Cravan. Scholars attribute Loy’s disaffection to the Futurists’ misogyny, but she was also critical of their chauvinistic attitude to their audiences—their assumption that they could orchestrate mass audiences without being subsumed by their unruly energy and power.